Horseshoe 2 Fire, Remembered

by Narca Moore

May 8: Today a fire sparked in the Chiricahuas and quickly blew into a large burn, driven by winds of 50 mph. It began in upper Horseshoe Canyon, close to the origin of last year’s Horseshoe Fire, and is being called Horseshoe 2. A Type 1 Fire Team has been dispatched and will arrive here in the morning. No lightning has been detected; the fire is almost certainly human-caused. Tom Arny very aptly characterized his view of the fire from Rodeo as “apocalyptic.”

(Photo by Brad Tatham)

At the start of the fire on May 8, Barney Tomberlin––one of Portal Rescue’s volunteer firemen who tackled the new conflagration––estimated those initial flames to be 200 feet high and the convection column of smoke to be 20,000 feet high.

May 9: Last night at 10 PM when Alan and I went to bed, the glow of the fire wasn’t even visible from our house––then we got a midnight call to evacuate. A glance out the window showed flames on the ridge immediately above us. As we loaded our two vehicles with our most valued items, the fire lit the red night so that we did not need a flashlight to avoid rattlesnakes. The fire roared continually, like a freight train bearing down upon us. (Miles away in Rodeo, DiAnn Matteson was also hearing that roar.)

We were lucky: a shift in the wind held the fire on the ridge a quarter-mile away. Soon––too soon––a red sun burned in the east.

In a single 24-hour period, this fire has burned about 8,000 acres, as much of the northeast face of the Chiricahuas as we can see from here. In one day, Horseshoe 2 burned about as much ground as last year’s Horseshoe 1 Fire accomplished in weeks. That is astonishing.

May 10: At tonight’s meeting with the Forest Service and firefighters from the Type 1 Fire Team, the Rodeo-Portal community learned about the team’s strategy for dealing with the Horseshoe 2 Fire. Extremely dry and windy conditions prevail. Communities across the West are facing what may be the most extreme fire season in memory.

May 11: On the western perimeter, fire was rolling downhill into Cave Creek Canyon between Cathedral Rock and Skull Rock, and the fire crew today set out to anchor a fireline between those two sheer cliffs, to prevent (we all hope) further incursion into Cave Creek Canyon.

Our friends in Rodeo have really come through, showing great kindness and hospitality to all of us evacuees. Izzy and Ramon Escobar and other Rodeo folk have manned the Rodeo Community Center’s evacuation center and cooked all the food given to people who sought refuge from the fire. Izzy said that they never had to ask for any supplies, because donations began to arrive immediately from all over the region, without anyone’s asking. The Food Basket, an organization in the Sulphur Springs Valley, provided us with ample food. The American Red Cross provided cots and bedding. And our good friends in Rodeo provided the labor, the organizational skills, and many, many offers of spare beds. Thank you so very much! Those tasty meals and cozy beds kept us going, and your concern and camaraderie met a different kind of need.

Here at the northern perimeter, the bulldozer operator and his crew, who put in the fire line 1/3 mile above our home and the Luckadoos’, did so in the midst of raging fire and high wind. Firefighters carefully judged just when the dozer could plow a little further, and then quickly pulled back whenever gusts of high wind brought a surge of flame too close. This is dangerous work. Only the willingness of these firefighters to put themselves in peril saved our homes. They are continuing to work on this very treacherous Horseshoe 2 Fire… and this is just the beginning.

May 15: My dear friends, my community––as you will hear at this evening’s 6 PM meeting at the Rodeo Community Center––the fire has progressed to a very serious turning point, triggering a shift in strategy among the firefighters. Horseshoe 2 has crossed the bottom of South Fork and is now burning uphill toward the Herb Martyr Road, the Southwestern Research Station, and Cave Creek Canyon. Firefighters have retrenched, and the new checkline along this northwest fire perimeter will be the road through Cave Creek Canyon.

(Photos by Narca Moore unless otherwise credited)

With the exceedingly dry fuels and winds predicted from the southwest, now gusting to 25 mph, there is little hope of stopping the fire before Cave Creek Canyon. Our best hope lies in slowing the fire’s advance and in reducing its intensity through very careful, very patient back-burning. This back-firing will be happening today in the Herb Martyr area and possibly in Cave Creek Canyon. All homes within the threatened area have protection in place.

Hold together, everyone. If you are in the area now threatened, please be prepared to leave, taking your animals, your valuable papers and computer, any irreplaceable pictures, and prescriptions. If you need help or feel overwhelmed, please let others know. We’ll take care of each other, and pull through this.

Today’s numbers: 22,110 acres burned; 20% containment; 614 people working on the fire; no structures lost; 3 minor injuries.

Expect the fire to be very active today and tomorrow. It’s a time of testing. Reach out if you need to.

May 16: Right now the fire is about 2 miles from reaching the American Museum of Natural History’s Southwestern Research Station. The distance seems small to me (after seeing just what this fire did on the first day!), but the difference now is that the fire teams are in place and actively controlling the intensity and speed of the fire.

The term “burn-out” is scary. A burn-out is planned for South Fork and a portion of Cave Creek Canyon, as far down the canyon’s north-facing slope as the main road. However, it is not a question of lighting a new fire that will rush upslope to meet the one now burning down. The Type 1 team’s full skill is being directed at controlling the intensity of the fire and setting up checkpoints where the possibility exists to limit its spread.

Here is how that strategy is being applied in South Fork: The crews first laid down retardant where they wanted to limit the fire’s spread, and then lit a fire––at night when humidity is higher and winds calmer––along the unburned ridge above South Fork, opposite the burned slope. The newly set fire then burned slowly downhill and met the upcoming fire. After a day or two of applying this strategy, a mostly beneficial burn is being achieved in South Fork. We don’t yet know the final outcome. The teams are under pressure to accomplish as much as possible before the next bouts of strong wind arrive.

May 25: The fire crews have had to use all their skill to moderate the fire wherever possible. When the fire jumps lines, control is lost and a much more severe burn results. Where it has been possible to moderate the fire’s intensity, a mosaic burn is being achieved. Elsewhere, crown fires are causing replacement of entire stands of forest.

June 1: Rose Ann Rowlett sent this photo and a report on her recent visit to South Fork, in the company of Linda Peery (USFS biologist), Salek (a hydrologist), and community members Dave Jasper, Richard Webster, John Yerger, and Reed Peters. Linda was asking local bird experts their advice on avoiding harm to nesting cavities as the USFS prepares for expected floods during the summer monsoon.

(Photo by Rose Ann Rowlett)

Fire crews have accomplished what has often seemed impossible under these windy, dry conditions. The last big winds, Wynne Brown said, gusted to 60 mph! I’m hearing from many people that fire crews “are my heroes!”

June 3: Just as we thought we were seeing an end to the fire and its attendant stresses, the Horseshoe 2 Fire has broken free of containment lines to move across Rock Creek Canyon and northeast toward Paradise, East Whitetail Canyon, and Chiricahua National Monument.

Unexpected high winds caused the fire to jump, generating flame lengths 200 feet high in a veritable firestorm. Those appallingly high flames released embers that caused two new fires to start near Saulsbury Saddle, more than a mile and a half from the containment lines. One of those new fires had grown to 400 acres by yesterday morning. Firefighters had to disengage from working the line in Rustler Park yesterday because the danger was too great. (Thus far, there have only been seven injuries, thankfully all minor.)

The Monument is temporarily closed to visitors, and residents of Paradise and Whitetail are being evacuated––for a second time, in the case of Paradise. One Whitetail resident was told yesterday that the fire was “still a day away” from her home.

June 4: I don’t think I can report dispassionately the latest developments in the Horseshoe 2 Fire, raging in the Chiricahua Mountains. When the fire jumped containment lines near Saulsbury Saddle, it roared through Rustler Park, Onion Saddle, Barfoot Park, and the high ridges so familiar to everyone who has roamed the high Chiricahuas. I am hearing from friends who are heartbroken. It is too soon to know just what has been lost.

Walt Anderson is a long-time friend and fellow artist who teaches at Prescott College. He was in Chiricahua National Monument when the Horseshoe 2 Fire jumped containment lines at Saulsbury Saddle and raged through Rustler and Barfoot Parks. His photos document that awesome, terrible event.

(photo by Walt Anderson)

(photo by Walt Anderson)

(photo by Walt Anderson)

In the other direction, fire raced in high winds through the village of Paradise, toward Whitetail Canyon, and Helen Snyder reported that last night Jhus Canyon was burning, next to Whitetail. So far people’s homes and historic structures like the George Walker House in Paradise have been spared, thanks to thorough preparatory work by fire crews.

After the two weeks of very hard work by Dugger Hughes’ Type 1 Fire Team, they have to feel terribly disheartened at the end of their rotation here, to see the fire escape. But without their valiant efforts, the outcome would have been so much worse. We likely would have seen the eradication of communities too.

We have been very focused, understandably, on the crisis in our backyard. Similar fires are raging throughout drought-stricken Arizona, New Mexico, and West Texas. The Bear Wallow Fire near Alpine, Arizona, just started, and blew to over 100,000 acres in only two days, as it roared through pine forest on the Mogollon Rim.

South of the border in Mexico, the entire Sierra Madre Occidental has been going up in flames, and Mexico does not have the resources, which we have, to deal with fire. So it is all just burning. “Sierra Madre” means the “Mother Mountain Range” and it is the heart of the habitats we so treasure in the Chiricahuas and other sky islands of the Southwest. The Sierra Madre has been an evolutionary cauldron for New World pine trees, oaks, and madrones. These mountains are the home of Eared Quetzals, Mountain Trogons, Thick-billed Parrots––and, of course, people.

June 5: You know you have been around intense fire way too much when you arrive in the gracious Deep South (as I just did), and see the stately magnolias, and dogwood, and flowering crepe myrtle––and all you really see is ladder fuel.

Friends are sending me reports from the daily fire crew briefings, so that I can continue to post. A new Type 1 Fire Team has rotated in––our third––so we are now in the fifth week of the Horseshoe 2 Fire. The new team is headed by Jim Thomas and is based in the Great Basin. They are taking on a fire that has burned 100,200 acres and is only 55% contained. They are entering a community that has been under great stress for a month, after repeated evacuations, and which is stricken by the grievous loss in recent days of a number of our most treasured places, when the fire broke through containment lines and cremated the high country.

June 10: Horseshoe 2 continues to surge north and west, driven by erratic––and sometimes unpredicted––winds. Always the winds. Crews have come to expect the unexpected: strong wind blows when little wind was forecast. Fire burns into the wind as well as with it. Steep terrain is crisscrossed by canyons, which suck wind into the inferno, against the direction of prevailing winds. Fire can sprout anywhere as it spots up to 2 miles away from the body of the fire, creating very dangerous conditions for the firefighters.

June 10-12––Wynne Brown’s report on Whitetail Canyon: All hell broke loose soon after I sent my last update. The wind picked up to 50-60 mph gusts that afternoon and blew so hard that it was hard to stand upright. The light in the Grills’ barnyard turned copper, the sun disappeared, and the smoke was so thick we could barely see Blue Mountain, much less The Nippers, Split Rock, or Maverick Peak. It whipped anything that was smoldering into flame, junipers exploded, and burning embers flew as far as 3 miles, igniting the ground, trees, dead stumps, and dry grass wherever they landed.

(photo by Wynne Brown)

(photo by Wynne Brown)

Whitetail became an inferno. Watching the smoke and, once darkness fell, the western glow, we knew for sure that every structure there HAD to be gone.

A fire team member arrived just before dark to assess the defensibility of the Grills’ ranch and let us know that, although the fire probably wouldn’t get here, we should be prepared to evacuate. So we scrambled to devise a list of who would release which livestock, which horses would go where, what truck/trailer combination would hold our combined eight dogs and seven cats, what about the chickens and the lame calf, where would the llamas go––and would the two camels load in the stock trailer?

Peter and Frances were able to set up a generator on the pump that feeds the cattle waterer and the house, and our first showers in a week were very welcome. Clean or not, none of us slept much Wednesday night.

The rest of Thursday was more dense smoke, more clearing flammables away from structures, more fire team trucks pulling in and out of the driveway, more discussion between the Grills and the fire team about using their pond for helicopter dips or just filling tenders, multiple trips to the hill a mile away to check cell phone messages and make calls, and most of all, trying to get real information about damage to our homes. The assessment team couldn’t get into Whitetail, which was still burning with flaming trees continuing to fall, hot rocks rolling down hillsides, stumps bursting into flame, the road thick with engines, tenders, and busloads of hotshot crews. I talked to a firefighter later, who grinned and said, “Yeah, we took some heat!”

By suppertime, Columbus Electric put in a new power pole so that this ranch could have power and the phone. Hallelujah!

On Friday (yesterday), the sheriff’s office informed me: My barn burned, but my house is fine.

(photo by Wynne Brown)

Thanks to the structure prep crews and the heroism of the firefighters who kept returning to the blaze after being beaten back by the heat, torching trees, and smoke––my house looks exactly the same as it did the week before all this started. Two of the 18 Whitetail residences burned.

On the surface, it might seem that the past six weeks have been nothing but loss: Yet, my gratitude list is nearly endless. I still have a house… and I still live in a beautiful, if wounded, area. But, most of all, I live in a buffer zone created by the loving, caring kindness of friends.

* * * * * *

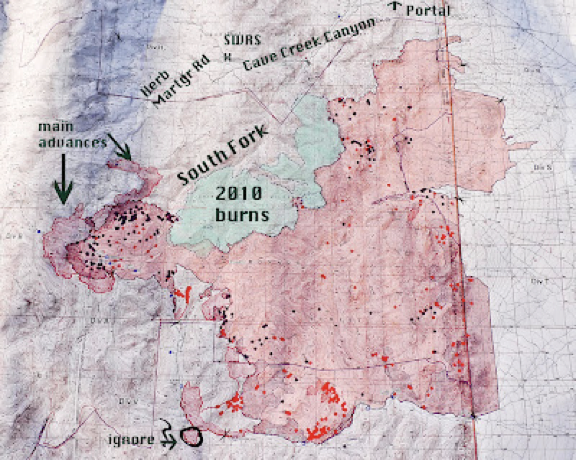

June 10: Breach of the fire line means that crews have to drop back to the next defensible place, shown by dotted lines on the June 10 fire map.

The new goal in the north is to prevent Horseshoe 2 from reaching Fort Bowie National Historical Site. The fire is burning into Chiricahua National Monument, and work continues there, with the goal of protecting both the monument’s resources and its structures. The fire’s growth potential remains extreme, and the difficulty of our terrain is of course also extreme.

One of the major fears about climate change in the Southwest is that forest types such as spruce-fir that need moister conditions will be driven completely off the tops of the mountains. Most of our plant communities are fire-adapted, and we expect them to recover, given time. However, mixed coniferous forest––which occupies the wettest, north-facing slopes of the high Chiricahuas––is not fire-adapted. Events like the Horseshoe 2 Fire could push that community (and its Mexican Chickadees, Yellow-eyed Juncos, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and Red-faced Warblers) right off the mountain top. We will likely lose the mountaintop refugia, and thus suffer a loss of richness, a loss of biological wealth.

I have heard scientists’ predictions about the changes in store for the Southwest, and about fire being the mechanism for bringing about those changes. But somehow I didn’t expect it to happen all at once, in two short months. Most of us aren’t geared to accept drastic change at the speed of light.

Although most of the community is solidly supportive and appreciative of all that is being done to help, I have come home from South Carolina to find talk of conspiracies between Border Patrol and firefighting agencies. People caught in the middle react, sometimes without logic or solid judgment. We need to rein ourselves in, stay as balanced and calm as possible. Long sieges are very wearing.

The fire crews are willing to face firestorms to protect what can be saved from incineration. They are operating with complete transparency, as anyone who attends the crew briefings can judge.

June 11: Containment efforts are working best down in the flats at the base of the mountains, and that is why the new fallback lines are drawn so far away from the currently active fire. The crews are bringing the fire to the fallback lines, where it can be managed.

As of this morning, the burn covers 134,615 acres and is 45% contained. 23 structures have been destroyed, most of them outbuildings. 1,153 people are working to put out the Horseshoe 2 Fire.

June 12: At last night’s community meeting with the fire team, Rich Harvey (an incident commander) emphasized the extremes that the firefighters are encountering in their dealings with the Horseshoe 2 Fire––unprecedented in his 32 years of experience. None of the professionals in this Type 1 Fire Team have ever seen such dry fuels.

Dead fuels are classified as 1-hour fuel (like grass), 10-hour fuel, 100-hour fuel, and 1000-hour fuel (a big, downed log). 100-hour fuel takes 100 hours to dry out enough that it will burn. Here in the Chiricahuas, 100-hour fuel is burning in only three hours, and that low a value has never before been seen by this team.

The amount of strong wind is blowing minds. Red-flag day follows red-flag day, and today we have another. Strong winds push fire into strong uphill runs, creating crown fires that take out stands of trees. The amount of energy being released in one hour’s worth of crown fire in the Chiricahua Mountains is the equivalent of the energy released by an atomic bomb. Such a fire chute occurred when Horseshoe 2 raged in only three hours from the Saulsbury Saddle line, up to and through Onion Saddle.

Yet, even with those serious extremes, a mosaic burn is being achieved in many areas through use of techniques that moderate the fire’s growth and spread, including lighting ridge fires at night to back slowly down into canyons, and meet the oncoming fire before it rushes up those same ridges. Of all the techniques tried by the teams so far, the backburning is working best on this fire, under these conditions. Moderating the fire not only promotes a mosaic burn, but also protects soils for future regrowth.

A photo of the junction of Rustler and Barfoot roads shows that many of the big trees survived intact, so some mosaic burn still happened, even in the intensely burned high country. We won’t really know the condition of the high country until the smoke clears, ashes settle, and the first rains start to revive the burn.

Raymond VanBuskirk hiked Bear Canyon behind our house, which burned intensively during the first night of the fire, and he found a few big madrone trees still alive.

We also learned more about one crew boss’s experience as they battled the holocaust in Whitetail Canyon, a situation vastly complicated by constantly changing high winds, which demanded the utmost in quick responses and flexibility. Plans had been carefully laid for protecting Whitetail, including a line laid by hand that joined the back road into Chiricahua National Monument, a dozer line, and structure protection. Then a big blast of wind from the south changed everything. One juniper flared and sent firebrands in all directions, and fire jumped the lines. A column of blazing hot smoke rose thousands of feet into the air, then rolled, and the column started to collapse. That is a firefighter’s nightmare because a huge collapsing column sends fire everywhere as superheated smoke hits the ground.

The worst-case scenario––killing the firefighters––was narrowly avoided in Whitetail when another big wind gust suddenly straightened the column. Firefighters were beaten back from Whitetail by these volatile and dangerous conditions. Firestorms involving collapsing columns of fire and smoke are quite rare, and this is only the second time in this operation chief’s career that he has ever witnessed one.

More than 1,200 fire personnel are now working on Horseshoe 2. They are on the lines 24 hours a day, in two shifts. People in the planning department work longer days than those out on the fire lines: they are spending 16 – 20 hours a day focused on strategy, as the fire moves and conditions constantly change.

The fire bosses said that two weeks of working on a fire like Horseshoe 2 is worth years of experience of working on more normal fires.

As horrific as the amount of burning appears on the fire map, and as huge as the area covered is, much of what was backburned is of low-to-medium intensity. Soils there will be in better shape, and recovery should be faster.

June 13: Firefighters confronting the Horseshoe 2 Fire in Arizona’s Chiricahua Mountains continue to encounter unprecedented fuel dryness. The values being found for both dead and live fuels are lower than ever before recorded in a wildfire, anywhere in the world.

Those record dry conditions are shared by the other Sky Island ranges in southeast Arizona. The record freeze last winter damaged or killed many oaks and pines, further drying them, and that freeze damage (coupled with extreme winter drought) has greatly intensified the fire danger.

The fire now stands at 148,505 acres and is 48% contained. The estimated containment date is still June 22. The fire’s growth potential and terrain difficulty remain extreme. Arizonans will never forget this summer of fire, beyond all the bounds of what we’ve known before.

We’ve all been holding our breaths that the other magnificent ranges will be spared the inferno being experienced by the Chiricahuas and the White Mountains, but a new fire began yesterday afternoon at the southern terminus of the Huachuca Mountains, in Coronado National Memorial, and already it is described as “massive.” It was estimated at today’s briefing to have burned about 3,000 acres in less than 24 hours. There were low whistles among the firemen when they heard how fast it’s moved. (For comparison, Horseshoe 2 grew to over 9,000 acres on the first day, when it was subjected to 50 mph winds.)

June 18: A major milestone has been reached with the containment of the western perimeter of the Horseshoe 2 Fire in the Chiricahua Mountains. Now the only very active part of the fire lies in the north, and the big fire camp at the Chiricahua Desert Museum in Rodeo is going to begin to break down today. The main operation will be moved to Willcox, closer to the active northern perimeter and closer to supplies. However, Rich Harvey cautioned crews that at this point expectations are for a quick finish––and it isn’t over, until it’s over. He noted that the only surprise now would be a bad one, and no one wants to see that. So, patiently, the work continues.

June 19: Last night and early this morning, fire crews working at the north end of the Horseshoe 2 Fire were able to tie in a line from Emigrant Canyon to Buckhorn Basin and to strengthen this line before the wind arrived.

That wind is a huge challenge today, for the Horseshoe 2 as well as the Monument Fire, but as of today’s meeting at noon, the lines were holding. The horrific wind has shifted from blowing from the southwest to the west, and that shift is favorable for the Chiricahua fire.

June 20: Yesterday’s raging wind, which gusted to about 50 mph, created serious challenges for fire crews working on both the Horseshoe 2 and the Monument Fires. In the Chiricahuas, those lines actually held! Incident Commander Jim Thomas congratulated the firefighters, saying that the success was the culmination of days of hard work well-done at the active north end of the fire. The crews held onto key terrain, and Horseshoe 2 is “still in the box.” As of last night, this fire had burned 213,511 acres and was 80% contained.

We are so, so close to seeing an end to this ordeal in the Chiricahuas. Let there be no surprises at this late stage!

In the Huachucas, the Monument Fire is 27% contained, and has become the #1 fire priority in the nation.

June 27, 2011: District Ranger Bill Edwards gave us an exemption to the Forest closure, so that we could conduct the annual census of Elegant Trogons. Parties were escorted by experienced firemen. Not surprising, trogon numbers were very low. About eight were found, all in South Fork.

My territory ran from about 1/3 mile below Maple Camp, up to that much-loved site, and it (and Richard Webster’s territory just above) turned out to be the most intensively burned part of South Fork that any of us saw. Even there, a few patches had been moderately burned, and several of the big maple trees look as if they will survive, even though many other trees growing on that same terrace have been reduced to charcoal.

When the trogon flew in, he came silently. For a few moments he paused in a scorched maple, then continued silently downstream, to be seen by Peg Abbott in the adjoining territory.

South Fork is resilient. It survives, with trogons.

Life from the ashes: In mid-September 2011, a meeting of 21 professionals convened at Rustler Park to assess its condition, and everyone was astonished.

Normally after an intense crown fire, such as the one that roared through Rustler Park, the soil is sterilized by the high heat, and almost no plants grow for a very long time, possibly years. Even the mycorrhizae––the fungi associated with plant roots which allow seedlings to germinate––need to be reintroduced to sterilized soils. (Often rodents perform that service!) No one was prepared for the lush growth of wildflowers and ground cover which greeted everyone at Rustler Park, especially around the old campsites and the start of the Crest Trail.

How can botanists account for the unexpected growth? After puzzling over the situation, they settled on this theory: the backburn done about two weeks before the crown fire blazed through must have removed enough fuel that temperatures at ground level never got high enough to sterilize the soil.

Botanists are seeing post-fire plants that they’ve rarely seen here, and the burnt aspen groves are surging with new growth. Reed Peters was impressed with the number of Arizona (Ponderosa) Pines that still show green on the knoll above the campsites. Keep in mind that we’ve all been expecting the worst at Rustler and Barfoot Parks!

And––yes!––a recent census of Spotted Owls in the Chiricahuas showed that not only do adults survive, they managed to fledge young this year as well.

(Pen & Ink by Narca Moore)